A-level Marine Science 2023

We’re now taking bookings for the January 2023 Marine Science A-level cohort

Start date online: Monday 16th January

Physical arrival in Malaysia: NOT BEFORE Saturday 04th February

Exam dates are:

Monday 24th April

Thursday 27th April

Monday 1st May

Wednesday 3rd May

Should you wish to make a provisional booking for either the January or June 2023 cohorts, please don’t hesitate to get in touch using the contact form.

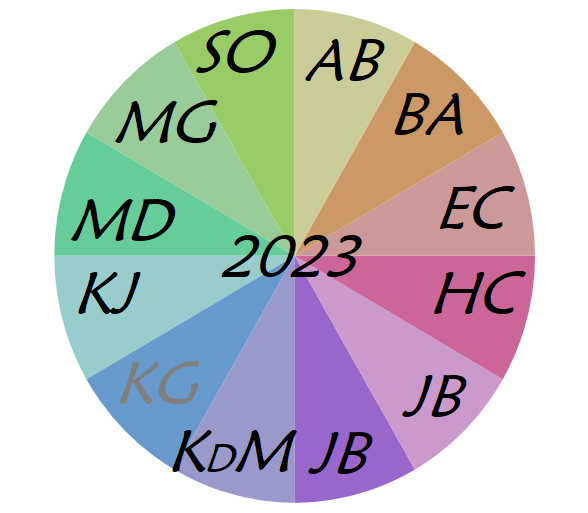

Correct as of 2022-11-30 HO

Correct as of 2022-11-30 HO

If your initials are shown in black on the chart above, then you have a confirmed place. Grey initials are provisional bookings only.

A-level Marine Science 2022

The Spring 2022 A-level Marine Science course is now underway!

Start date online: Monday 10th January

Physical arrival in Malaysia: NOT BEFORE Saturday 12th February

Exam dates are:

Tuesday 26th April

Thursday 28th April

Tuesday 3rd May

Tuesday 10th May

Should you wish to make a provisional booking for either the Autumn 2022 or Spring 2023 cohorts, please don’t hesitate to get in touch via the booking form.

CORAL FRAGMENTATION

In the recent light of the controversy in coral fragmenting, we would like to respond to it as TRACC has been working in coral restoration projects for almost a decade now, and we have done numerous amounts of coral fragmenting. Although TRACC performs many other conservation projects, from turtle conservation to crown-of-thorns population control, our main goal being on Pom Pom Island is to re-build the damaged house reef from historical blast fishing 20 years back.

In the recent light of the controversy in coral fragmenting, we would like to respond to it as TRACC has been working in coral restoration projects for almost a decade now, and we have done numerous amounts of coral fragmenting. Although TRACC performs many other conservation projects, from turtle conservation to crown-of-thorns population control, our main goal being on Pom Pom Island is to re-build the damaged house reef from historical blast fishing 20 years back.

The level of obliteration blast fishing has done at Pom Pom has decreased coral cover an average of less than 5% throughout the island’s reef. Interestingly, some suggest that in an irreversibly damaged ecosystem, the alternative to improve it is to modify and design a new ecosystem that would help it to promote the biodiversity and life that depends on it. However, at TRACC we look in many other factors before launching a restoration project, especially when it involves coral propagation. Before diving into the factors involved in our coral propagation projects, one needs to understand the projects itself.

The two projects that we would like to discuss are our Coral biscuits, where coral fragments are placed into a cement mix molded by take-away plastic containers and Coral epoxy, where coral fragments are effectively glued onto artificial reefs with aquarium grade epoxy.

CORAL BISCUITS METHOD

CORAL BISCUIT METHOD

CORAL EPOXY METHOD

CORAL EPOXY METHOD

‘Corals of opportunity’ – fragments as a result of natural and anthropogenic disturbances are utilized by TRACC into the two projects mentioned earlier. The reefs around Pom Pom Island are highly dynamic and often form on slopes that are almost walls. TRACC aims to create a stable substrate through artificial reefs onto a reef that is limited in coral growth by loose rubble often called ‘killing fields’. Subsequent ‘corals of opportunity’ are holstered onto the stable platforms to survive and thrive, increasing the biodiversity of the reef.

Speaking about biodiversity, the concern about coral fragging also stems from reduction in genetic diversity by having clones of the same colony throughout the reef. However, in regards to the projects, the corals are chosen randomly from the reef and are fragged to smaller fragments until all of it is utilized, hence the project maintains the genetic diversity and uses the natural diversity of corals in the area. Furthermore, the amount of corals planted through fragmentation compared to natural recruitments is insignificant, but the importance of the project is to facilitate the natural processes by helping in stabilizing the loose substrate. This means that the initial coral fragments ultimately provides for a greater abundance and diversity of scleratian corals compared to a possible recovery of ‘killing fields’ of rubble would be dominated with initial soft corals. This rings a bell as the saying goes ‘the end justifies the means’.

Another main reason why TRACC would not merely collect broken coral fragments and utilize them, but choose certain ones and fragment them to smaller fragments to supply the coral planting project is due to the health status of these fragments. The reality for the broken coral fragments laying on the reef is that they have a high potential of acquiring multiple diseases, or without a stable substrate, will die.

On Pom Pom Island, it has been observed that fragments laying on the substrate are often present with Drupella snails, which tend to transmit disease upon feeding. This renders the projects to selecting only healthy fragments for coral propagation where most of the coral supply of the coral epoxy project comes from ‘coral bushes’, a horizontal version of the common ‘coral tree’ practice. The ‘coral bushes’ holds fragments away from the substrate, out of the reach of the corallivores such as crown-of-thorns starfish and Drupella snails. Although ‘corals of opportunity’ are abundant but coral fragments are limited on the ‘coral bushes’ because they require maintenance. Hence, coral fragging used in the coral epoxy project is done so as to propagate corals on the artificial reefs while maintaining the stock from depletion. Although it seems like the best idea to maintain diversity by using all the ‘coral of opportunity’ found on the reef, however, once a disease spread throughout the project, the restoration effort goes to vain.

Another factor one should consider in coral propagation projects is the functionality of the scleratian corals. Sometimes, coral propagation is not focused on the actual diversity but the functions each coral genus can provide. A coral ecologist would tell you that some coral genus are pioneer individuals just like grass on land while other slower growing coral genus are the successors. Hence, to resemble this form of succession, it is definitely not merely to jumble up all the forms and species of corals into one patch of restoration. We need to understand the levels of succession in coral reefs of the region.

Additionally, in the two projects mentioned in this discussion, coral propagation relies on artificial reefs for a stable platform. However, artificial reefs are not immortal and it requires the assistance of natural reefs to be bonded by the calcium carbonate secretion of scleratian corals. At TRACC we desire to reduce the time taken for natural coral growth and use the knowledge of coral fragmenting to bond adjacent units of artificial reefs. This is achieved by fragmenting corals in the coral epoxy project and attaching them in two adjacent artificial reef units underwater. The fragmenting allows the corals to grow faster than normal and with the fact of being clones, they recognize each other and subsequently merge as one colony again. The merging helps to reaffirm the bond of the artificial reefs and with many attempts of this they form structurally sound units just like threads in a rope.

With great power comes great responsibility. The knowledge of coral propagation and restoration should be used wisely. It is of utmost importance to understand the surrounding environment and its intrinsic variability and challenges before attempting to launch a project regarding the subject matter. One needs to understand the existing restoration methods and their advantages and disadvantages. From anecdotal records, TRACC has seen many changes in the reef and Pom Pom Island does not play by the rules. What works or fails on the island wouldn’t necessarily do the same elsewhere due to the multitudes of environmental factors. The training for the projects at TRACC most often begins with the appreciation and preservation of the living reef. The steep angle of the reef slope is a constant reminder that environmental projects should be well planned out, including a retrieval plan for any projects that have failed.

Although monitoring in many of the environmental projects worldwide may seem to incur additional cost but it is a primary way to obtain answers from our environment. The advantage of working on the same reef on the island for almost a decade now is that we get to learn that reef restoration is a very difficult subject. TRACC has employed endless peer-reviewed papers, expert elicitation, and trial and error to come to the position we are in as a conservation centre aiming to restore the small but mighty patch of reef we are custodians of. Because of this, we not only adopt best-practice management, we also constantly monitor our reefs to ensure the work we are doing is beneficial to the continuity of coral reefs. To adapt to the changes and to adopt restoration methods is very important to keep the environment we protect as the number priority. Monitoring never ends at TRACC

A-level Marine Science 2019 Results!

The 2019 A-level Marine Science cohort did amazingly well this year.

13 students graded A*-C, with 5 A grades and 4 A*. Two candidates scored 92% cumulatively over 4 exams - an exceptional achievement.

They are a credit to themselves and their wonderful teacher - Maddie Davey (PhD).

These new grades bring our cumulative totals from 2013-2019 as follows.

A-level Marine Science 2020

Tracc is very pleased to introduce the teacher for the 2020 Marine Science A-level

Dr Stuart Maudling

Stuart is an expert in fish nutrition and did his PhD on the use of dietary immuno-stimulants to manage stress in fish at the University of Plymouth, UK.

He is currently the head of biology at a British grammar school teaching both A-level and IB Diploma.

We look forward to welcoming him to Pom Pom as well as assisting him to guide the 2020 students to achieve their best grades possible.

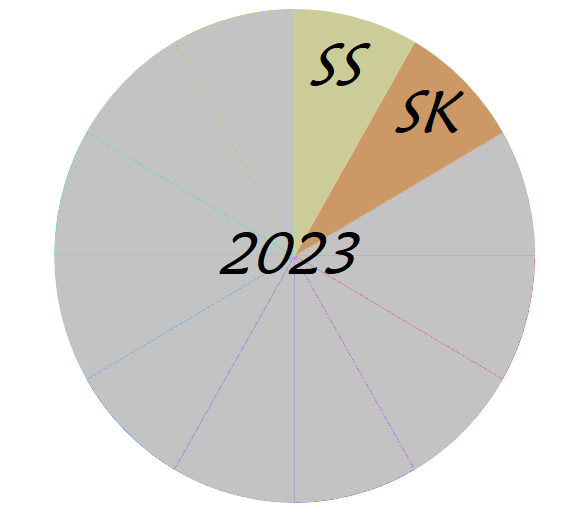

Confirmed HO 02-11-19

(02-11-19) The January 2020 cohort is now full. If your initials are not shown here you do not have a confirmed booking. If you wish to pre-register for the A-level 2021 or have any questions please do get in touch.

FISH MARKET EXCURSION THROUGH THE EYES OF A STUDENT.

The array of tables at the fish markets were like a morbid map of Borneo's waters.

Approximately 93.4 million tonnes of fish are caught annually, according to the 2014 estimation of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. This is a unsustainable number causing massive damage to populations and ecosystems. However, fish are a vital food source worldwide, and the fishing industry is a source of income for many. The clash of environmental impacts versus human necessity is something which I have morally battled with for a long time, but really facing these issues in the fish markets of Borneo drove things home in a way I had never expected.

Click on the image below for more.

The array of tables at the fish markets were like a morbid map of Borneo's waters. As marine animals are adapted to live in different places, behave differently, and consume different things, you could see where in the sea each animal must have come from. Different fishing methods are used to catch animals based mostly on these adaptations. The main fishing methods we identified benthic trawling and purse seine fishing, which were used to catch bottom-dwelling and open ocean species.

Benthic trawling is a horrendously destructive method of fishing, and can in no way be done sustainable. It involves dragging a net attached to a heavy object along the seabed, in order to catch commercially valuable animals on the seafloor. However, it destroys anything it encounters, reducing hugely important habitats like coral reefs to rubble. It also catches far more animals than those that are aimed for. So, when trying to catch something like shrimp, a devastating number of other animals are caught and severely damaged or killed, which are often deemed to be without commercial value and so are simply discarded. Some estimates suggest that up to 98% of trawling bycatch is discarded. Animals caught in this process can end up choking on the sediment of the seabed, something which I learned graphically from looking at smaller sharks at the fish markets. So many had mouths and gills full of mud and sand, and eyes with burst blood vessels.

Purse seine fishing involves using a vertical net with floats at the top and ropes at the bottom, which are used to close the net like a drawstring. It is used to catch species which live away from the seabed and coast, like mackarel. Purse seine fishing can be sustainable if smaller nets with large mesh are used, to catch fewer fish and allow smaller fish to escape. However, it looked as though unsustainable methods were widely used as there were no large fish of some species (large fish indicate that members of the population survive long enough to grow to full size).

It was also obvious that some fishing took place too close to coral reefs, as many reef-associated species could be found. Maybe the most jarring thing for me was that these species in particular have become very familiar to me through diving on Pom Pom, and to see them lifeless on tables felt pretty wrong. I'm used to seeing parrotfish swimming with their little side fins, boxfish floating by looking bemused, bluespotted ribbontail rays gliding elegantly through the water or skulking under rocks. It's strange how almost unrecognisable these familiar faces look once the life has gone.

The last fish market we saw was the midnight market in Kota Kinabalu. The lights turn on at midnight and the most hectic environment I've ever witnessed comes to life. This is a commercial fish market, in which buyers purchase vast quantities of seafood animals to be prepared and packaged, ready to be put on the first flights out of Kota Kinabalu (usually around 6am). With serious money on the line and little time, the atmosphere is electric as fishers throw around 35kg boxes of produce like they weigh nothing. People in yellow wellies were the buyers, who weighted and bought boxes by placing slips of paper on top. These were then stacked on trolleys, which weaved in and out of the sea of boxes to be loaded onto waiting trucks. On the sides were boxes full of less valuable bycatch, emphasising just how much is wasted by some fishing practises. The sheer scale of this single commercial operation really drove home just how much we are taking from the ocean to me. We saw hundreds of 35kg boxes in the short time we were there, which helped to make the impossibly large number of 93.4 million tonnes feel far more real.

These markets represented many of my first sightings of animals. I've never seen a shark in the wild before, but now I've seen hammerheads, blue sharks, guitar-head sharks, and even a big-eyed thresher shark. All dead. To call this heartbreaking would be an understatement.

With all of this being said, I cannot express enough how we have no right to pass judgement on the people at these markets. The fishers were so kind and accommodating to us, showing us their catch and answering our questions. Even when we were in their way, there was no gesturing or shouting. They were so keen to make a connection with us and find out where we were from. We must also remember that fish are an incredibly important resource for the global population, with hundreds of millions of people relying on them for income and as a primary food source. They are packed full of protein and nutrients, vital to some areas where these cannot be matched in other available foods. It is neither pragmatic nor moral to simply say that fishing must stop - fishing is a necessary practice, but the way it is being done now cannot continue if we want there to be fish in the sea in the future.

We need to improve fishing practises, with an emphasis on sustainability. We must end the devastating fishing practises, such as trawling, and replace them with sustainable methods. Time must be given to allow stocks to replenish. Governments need to put initiatives in place to provide opportunities for fishers who may be put out of work. However, doing this will cause deep and tremendous sorrow for a huge number of people, who have been fishing for generations. We cannot just ignore this - there is a huge amount of culture and depth of feeling to consider. These people cannot be left high and dry, or expect to drop this industry overnight. We cannot wade in and expect such dramatic changes to take place. But without any changes, fish and fishing opportunities will simply vanish for (not too distant) future generations.

Basically, the fishing industry has within it huge problems, but there is no easy answer to reverse the damage caused without impacting many human lives. I certainly can't think of a way forward to support both environmental and human interests. All I know for certain is that something needs to change.

Written by: Althea Piper

Images by: David Eriaud and Aneata Friend.